Honey Fungus

15 July 2009

The least welcome sound to any gardener? Four syllables: honey fungus. I suspected it the moment I saw the rose that accompanied my working life for 20 years, three feet from my desk, winking its harlequin flowers at me all summer through the window, sicken and, within ten days, die.

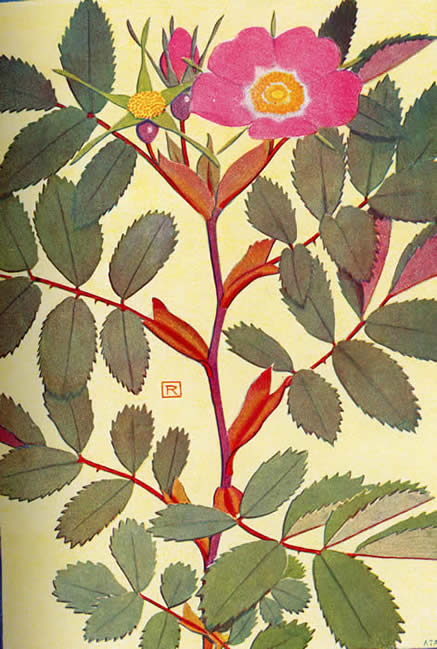

It was the so-called climbing form of Rosa mutabilis, the slender Chinese rose that changes colour from orange in bud to deep crimson-pink as the simple wide-open flower, once pollinated, fades and falls. I planted it in the wall-corner to the left of my window, knowing that its slender structure of smooth purple stems would not get out of hand and that its flowers would entertain me for much of the year. I liked its story, too, as Graham Stuart Thomas tells it. It was given by Prince Borromeo, the fortunate gardener of those two romantic islands in Lake Maggiore, Isola Bella and Isola Madre, to Henri Correvon, the Swiss botanist whose Flore Alpine excited me in youth like no other flower book. When you see this plate, one of his friend Philippe Robert’s illustrations, you will see that it lies at the heart of what we call Art Deco. Robert did not paint Rosa mutabilis, alas.

My plant on the wall grew to nine feet, hardly qualifying it as a climber, but beautifully framing the window, invaded from the other side by grape-vines.

The rose is dead and the vines are sick. Wisley confirmed that the root I sent to the pathologist was killed by Armillarea mellea – though its black bark, peeling off to show a layer of white mycelium, was scarcely open to other diagnoses. I remembered then that the Japanese anemones in the bed under the windows had once grown so tall that I peered out through their white flowers and vine-like leaves; then next year had barely reached the sill. That was nearly 20 years ago. Had the malignant fungus been lurking along the base of the wall all this time?

The document that the R.H.S. sends out to victims is full of data but little encouragement. The black bootlaces of

St James's Park

13 July 2009

St James’s Park must be on the short list of Britain’s most beautiful landscape gardens. The views in both directions from the bridge over the lake outdo anything that even Blenheim, Stowe or Stourhead have to offer. Buckingham Palace is no beauty, but its bulk framed in willows and nudged by a metasequoia closes one memorable view, while the wildly romantic domes and pinnacles of Whitehall to the east evoke an imperial mirage. Oddly enough the arc of the London Eye behind only adds to the effect: a window from the world of ducks and willows onto an exotic empire.

The park of course has magnificent trees, principally London planes, presumably planted in the last phase of its development in the 1820s when John Nash was in charge, not only of building the palace and the even more palatial Carlton House Terrace, but of the gardens they overlook. Over the past 10 years or so they have been restored (with the advice of the Garden History Society) to a version of their original planting. It comes as a surprise, and a reminder of how (not to beat about the bush) primitive gardening ideas were in those days, and how far we have come in the

Lucy’s wedding

24 June 2009

Another wedding in the family to garden for with happy anticipation. This time a September one. There should be no shortage of flowers in late September; it is winding down time, when we accept the tousled look of plants that have finished growing and are bent on child-bearing. What could be more appropriate?

The church at Saling is a hundred yards from the house, through a gothic door in the garden wall. The walled garden will be brimming with pink japanese anemones, pale purple michaelmas daisies and white cosmos, Cambridge blue bog sage (a good earthy name for the graceful Salvia uliginosa) and the equally graceful purple Verbena bonariensis. The roses will be in their second flush; pink Felicia, white Iceberg and pale flesh-coloured Autumn Delight, which at the moment needs support for its abundance.

|

honey fungus can travel a metre a year, they say, and reach as far as 30 metres. I look despairingly round at the plants within a 30-metre radius. They include magnolias (susceptible), a cedar (highly susceptible), a number of roses, a quince, a crabapple …….. Do I see wilting shoots, or just imagine them?

‘There is no treatment available’ goes the usual rubric – with a subtext, I always feel, of ‘to mere gardeners like you’. Bray’s Emulsion, the old panacea, has been condemned as unsafe (or at least, by E.C. standards, untested). How many gardeners has it killed or disabled? I think we should know. You can still get creosote, a rough and ready version, but woe betide you if the police sniff it around your plants.

Meanwhile the ancient grape vine on the gable is dying, and the next one along the front of the house is looking poorly. Does some witch-doctor know a spell?

introduction, choice, breeding and disposition of (particularly) shrubs and perennials. One can too easily overlook all the hard work put in by nurserymen, landscapers and critics that have given modern gardening its unprecedented polish. Infinitely more is known today, infinitely more cultivars are available today, design ideas today take for granted a body of sophisticated taste and knowledge that far outstrips all the experience of the old school. Whether we do it justice is another matter.

The garden planting in St James’s Park, faithful to the taste of the 1820s, is frankly a mess by today’s standards. It consists largely of curvaceous island beds low on the slopes from the Mall down to the lake, in which perennials are mingled with what feels like naive enthusiasm among shrubs that mostly have one season (if that) of beauty.

The ‘one of this, one of that’ school of planting dates back much further than Nash’s time; in 18th century flowerbeds the plants, as varied as possible, were apparently kept well part, with an effect we would find woefully spotty. ‘Apparently’ because this is how they appear on plans, and where is there a realistic painting of an 18th century border? In St James’s Park they are allowed to fill out and cover the ground in the modern manner; what is missing is modern colour discipline – and of course the best new plants.

It is a praiseworthy idea, to show us the park that Nash designed rather than a modern version. But a park is not a museum; it is a pity to confuse the two.

Red penstemons and deep pink sedums, brown chrysanthemums, the turning leaves of vines and Euphorbia palustris, and the broad dome of the Koelreuteria above the churchyard gate door will be the warm notes. All this will be enriched with salvias, the autumn gardener’s standby. Bright pink S. bethellii will be chest-high by then, and I am anticipating wonderful blues and reds from the cuttings I took at Lochinch last autumn. S. madrensis, tall and yellow, partners tall blue michaelmas daisies, S. calcaliifolia is bright blue and S. ‘Guanajuato’ a shrill rich blue that calls across the garden. Clematis will enamel shrubs on the walls that have done flowering. Hydrangeas will be mellowing to indeterminate colours – and the apple trees will be full of fruit.

A reception in the concentration of flowers in the walled garden is Wedding Plan B. Plan A, for a day with no risk of rain, is to walk down to the Temple of Pisces and party round the Red Sea in the middle of the arboretum. There are no flowers here in autumn, just the mellow colours of late-summer trees, secluded in a glade that shuts out the world of roads and fields. Lucy once played Titania. I think she sees her bridegroom as Oberon.

|